Table of Contents

Birthing and Breeding

Birthing and breeding season takes place December through March. Adult male seals (bulls) and large sub-adult male seals begin to arrive in late November, with most arriving in December.

As they arrive, males lay claim to a section of the beach – a claim that is frequently challenged. Typically, a dominant alpha male bull hangs out with 2 to 3 sub-dominant beta males to control each section. While dramatic battles may arise as the seals claim their section of the beach, most of the face-offs for dominance are settled with intimidation. Only a small percent of confrontations result in a significant battle. This helps to conserve energy required for their long fast while on the beach for the duration of the season.

Pregnant females begin arriving in December with most coming in January. Births occur a few days after arrival. Births occur on the beach, often at night. The pup nurses from its mother for four weeks, quadrupling its birth weight to around 300 lb (135 kg). The mother’s milk is very rich, reaching around 60% fat by weaning time. The mother will lose 2 lbs (0.9 kg) for every lb (0.45kg) the pup gains, eventually reaching a loss of about 40% of her original weight. Twins have never been documented, although some mothers will foster an additional lost or stranded pup(s).

During the last week of nursing, the mother comes into estrus and mates. Shortly thereafter she goes to sea, leaving her pup behind – abruptly weaning them by desertion. There is no evidence that that mom-pup relationship plays any future role in their lives. The weaned pup remains in the rookery, fasting, for an additional 8 to 10 weeks.

By mid-March, most of the adult seals are gone, leaving the pups behind. As the beach becomes less populated, the pups start exploring the shallow water just off shore. Clumsy with their newly acquired weight, it takes some time before they are able to swim well. They mostly go into the water at night. This helps to prepare them for dives at sea where it will be dark all of the time. Most depart by late March or early April.

Mating and Gestation

Females come into estrus and begin mating about 24 days after giving birth. However, the fertilized egg does not implant in the wall of her uterus for about four months, a phenomenon called “delayed implantation”. This enables the adult female seal to go to sea and regain some of the weight she has lost during the birth and nursing process. Since the seals’ gestation period is seven months, this delay means that the young will be born after the female reaches her breeding ground the following year. Adult females may mate several times before returning to the ocean.

Delayed Implantation

Shortly before a female leaves the rookery after birthing and nursing her pup, she will mate several times and become pregnant. She leaves the rookery for two to three months, returning in April or May for a month on the beach to molt. Once she departs after molting, the fertilized egg, which has developed into a cluster of cells, known as a blastocyst, attaches to the uterus. At that point, the seven-month gestation period begins and the embryo starts to develop.

This delay in the attachment provides several important advantages:

- The female departing the beach after birthing has lost about 40% of the weight she had when arriving on the beach. During her time at sea before the molt, she is able to regain some of her weight without simultaneously nurturing a fetus.

- Similarly, she is able to fast during the Spring molt without the resource loss required by gestation.

- Perhaps the most important advantage of delayed attachment, is that it serves to synchronize birthing during the winter months. And, it provides for variation in the time of breeding, especially for the first pregnancy for young females.

The majority of the females who give birth during the winter months are bred in or around February. However, 15% to 20% of births each year are to new mothers, juvenile females who are not in the rookery during the birthing/breeding season. They are bred at other times, but, like all juveniles, they come to the rookery to molt in April or May, at the same time as the experienced females. With attachment occurring on departure from the Spring molt, the gestation period of these new mothers-to-be begins at the appropriate time. They will give birth on schedule the following winter.

Pup – less than 1 month

Weanling – 1 to 12 months

Super Weaner – 1 to 12 months

Yearling – 1 to 2 years

Age Classes

Northern elephant seals can be categorized into multiple classes based on their age and gender. Females mature earlier than males and reach adulthood several years before males do.

Juvenile – 2 to 5 years

Sub-adult Male – 5 to 8 years

Adult Female – Over 3 years old

Adult Male – Over 8 years old

Lifespan of an Elephant Seal

As with most wild animals, an elephant seal’s life is fraught with danger. As visitors to the rookery can see during the birthing season, a number of seal pups do not survive. High seas can carry a pup out into the ocean, which they cannot withstand until they are a few weeks old. On the beach they can be unintentionally crushed by a bull, or starve because they have been separated from their mother and failed to find a surrogate. In a year with mild weather, the loss of pups at Piedras Blancas is around 5-7%. In a bad year, with major storms from the south, the loss can be as high as 20%. The rest survive to go on their first voyage. However, only 50% survive their first year.

Other than pups, very few seals ever die on the beach. Loss in the ocean, however, is significant. However, we know few details about what the seals die from.

Known predators are the great white shark and the orca or killer whale. Some seals are caught in fishing nets and drown. Some likely die from failure to forage successfully, disease, or parasites.

What is known is that many do not return. A study at Año Nuevo showed that only about 2 of 3 males survived each year and that, for most of their life span, 6 of 7 females survived each year. The more than double mortality rate of the male may be the result of their foraging preference in areas rich in orcas.

For those few who do survive, the maximum lifespan for male northern elephant seals is age 14; for females it is to age 20 or more.

Fasting

Except for nursing pups, all of the seals in the rookery are fasting – no food and no water for their entire stay. They survive by metabolizing their blubber, providing energy, nourishment, and water. Water is one of the by- products of using fats for energy; this process is called metabolic water production. At the same time, their highly efficient kidneys concentrate their urine to minimize water loss.

The seals lose water mainly through respiration. They breathe in cool air, which heats up to body temperature (slightly higher than ours) and absorbs moisture. When they exhale, any water in that breath would be expected to evaporate.

However, they conserve water in two important ways. First, they are able to minimize water loss by not breathing 60% to 70% of the time. In addition, they are able to capture and recycle much of the water in the exhaled air through countercurrent heat exchange. Evaporation is reduced as the moisture in warmer exhaled air condenses while passing through the cooler membranes lining the complex turbinate structures of their nasal passages.

Fasting serves a number of purposes. By not foraging in the area of the rookery, they greatly reduce the attraction of predators, making access to the beaches much safer. Also, for the molt and nursing periods, fasting allows those activities to consume a minimum of time, maximizing their foraging time at sea.

During the breeding and pupping season (December to March), adult male elephant seals come ashore to establish and maintain mating dominance over other males. During that time, they lose 40% of their body weight-up to 2000 lbs (900kg). If a male were to leave the beach, he would lose his mating advantage. Fasting as long as three months, one of the longest mammalian fasts, ensures the male retains mating access to females.

Female elephant seals nurse their pups for about a month. Leaving the rookery to forage could result in a female losing her pup, a major cause of pup mortality. Weaned pups (weanlings) remain on the beach after their mothers depart. They are able to fast for 8 to 10 weeks in the predator-free zone of the rookery before venturing into the sea to forage.

Molting

Beginning in late March and extending into September, each of the seals, with the exception of the weaned pups of that year, will return to the rookery for a month to grow new skin and hair. Because the seals do not circulate blood next to their skin while in the ocean, they cannot grow new skin and hair cells continuously as we do. Instead, they come onto land where they are surrounded by air instead of cold water, which increases blood circulation next to the skin. The seals grow new skin and hair, shedding their old coats in the process. They can look very ratty during this period, but they are doing fine.

The number of seals on the beach is largest in April and May, with adult females and juveniles of both sexes arriving to molt. The beach may not seem as full as it did during birthing, since they lie so close together.

Each female and juvenile seal will take about a month to molt, and most will be gone before the sub-adult and adult males arrive to molt sometime between June and September.

An Elephant Seal’s Deep Dive

When diving to hunt, the northern elephant seal first exhales, emptying its lungs of almost all air. This reduces buoyancy and protects the seal from the bends (decompression sickness). All of the oxygen used to provide the energy needed during the remainder of the dive is stored in the red blood cells and the muscles. At the beginning of the dive the seal swims with its tail fins, however during the rest of the descent, almost 90% of the time the seal simply glides.

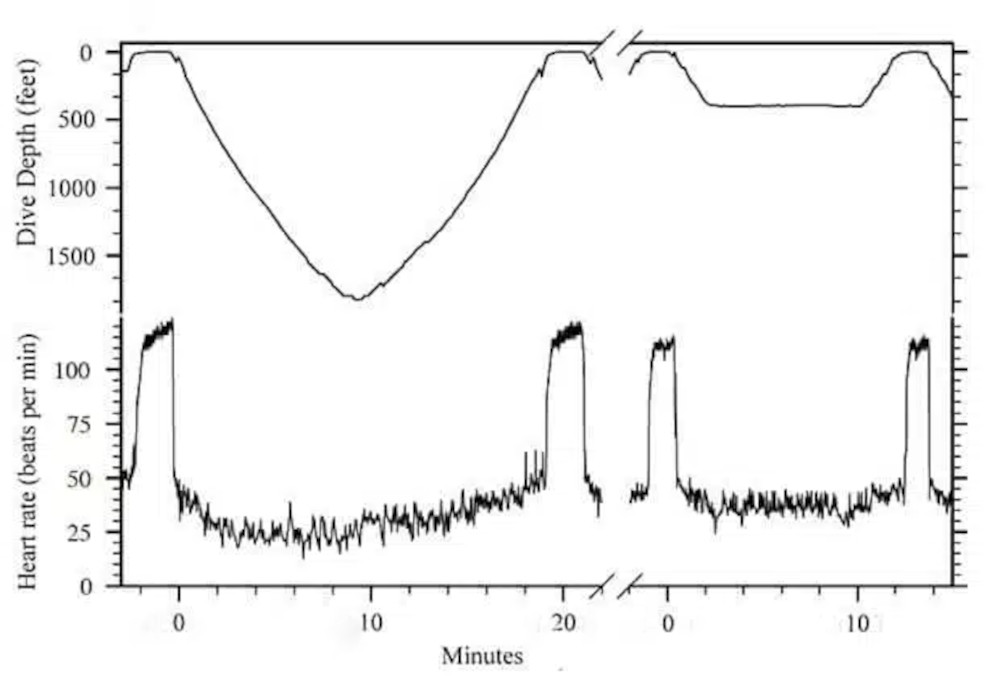

To enable the long period without breathing and the rapid recharge at the surface, the northern elephant seal has a very different surface and underwater metabolism. At the surface the seals have a heart rate of between 80 and 110 beats per minute. When diving, the heart rate drops typically to one-third the surface rate and occasionally as low as 3 beats per minute. Circulation becomes limited almost completely to the heart and the brain so that oxygen consumption is minimized.

Dive profiles are approximately V-shaped with vertical speeds of 2 to 5 mph (4 to 8 kph). A seal will swim approximately 15,000 to 20,000 miles (25,000 to 32,000 km) each year. They are capable of swimming at speeds up to 10 mph (16 kph) but usually travel more slowly to conserve energy.

When away from the continental shelf, seals dive somewhat deeper during daylight hours than at night. This probably reflects the behavior of the prey, approaching the surface at night, rather than the effects of reduced light on the seals.

Elephant seals have a very large volume of blood, allowing them to hold a large amount of oxygen for use when diving. They have large sinuses in their abdominal veins to hold blood and can also store oxygen in their muscles with increased myoglobin concentrations in muscle. In addition, they have a larger proportion of oxygen-carrying red blood cells. These adaptations allow elephant seals to dive to such depths and remain underwater for up to two hours.

The dive response slows down the seal’s heartbeat (bradycardia) and diverts blood flow from the external areas of the body to important core organs. Seals also slow down their metabolism while performing deep dives.

Elephant seals have a helpful feature in their bodies, known as countercurrent heat exchange, which helps them conserve energy and prevents heat loss. In this system, arteries and veins are organized so as to maintain a constant body temperature. Heat is transferred from the warm blood flowing in arteries to the cooler blood returning to the heart in veins, thus keeping the seal warm.

The Dive Response

Like all seals, elephant seals undergo a set of physical changes when they dive – called the dive response. The dive response includes a significant drop in heart rate, constriction of blood vessels in the periphery, and cessation of breathing (apnea). These biological adaptations protect the elephant seal from excessive heat loss and maximize their survival time without breathing. The figure (Andrews, 1997) shows the change in heart rate at sea for both deep and shallow dives.

Interestingly, the seals also slow down their breathing on the beach, just as they do when they dive. There is a similar, if less pronounced, change in heart-rate. Apnea regularly occurs on land for periods of 8-10 minutes in adult seals. (This is a shorter period of time than during the dive at sea.) Even pups and weanlings use apnea as a means to conserve energy. Visitors often notice that seals are not breathing and worry that they are dead.

Oxygen Capacity and Utilization

Oxygen is used by all mammals to support metabolism and is carried in three ways – as a component of air in the lungs, attached to hemoglobin in the red blood cells, or attached to myoglobin, a similar molecule to hemoglobin that is fixed in the muscle.

Elephant seals have extraordinary adaptations which allow them to transport, store and use oxygen with extraordinary efficiency. The dive response enables them to slow their heart rates and shunt blood flow away from the extremities to essential organs like the brain and heart.

When elephant seals dive, they exhale almost all the air in their lungs, allowing them to become negatively buoyant. They are about 22% blood volume by weight, as compared to about 8% in humans. Their blood is richer in hemoglobin, with a concentration of about 20-24 gm/dl, compared to 12-17 gm/dl in humans. Similarly, the percentage of red blood cells by volume in the blood is about 60%, compared to 35-50% in humans. In addition, the heart and skeletal muscles of elephant seals have a density of myoglobin, a molecule similar to hemoglobin, that is more than 8 times more concentrated than it is in human muscle. Because oxygen is stored in their muscles, the heart is able to conserve oxygen by circulating less blood to muscle tissue.

While these mechanisms allow the elephant seal to start the dive with a large supply of oxygen, the elephant seal has the ability to utilize almost all of it on every dive. Their tolerance for low blood oxygen levels greatly surpasses that of humans and other mammals, ending dives with oxygen saturation levels in the venous blood as low as 8%.

This extraordinary capability allows them to dive to great depths and to surface only briefly between those dives. 90% of their time at sea is under the surface — most of that time 1,000 to 3,000 feet (300 to 900 m) deep.

Sensory Ability

Like all seals, elephant seals undergo a set of physical changes when they dive – called the dive response. The dive response includes a significant drop in heart rate, Elephant seals forage at great depth where it is very dark, even during the day. While there is no evidence of any echolocation ability, foraging appears to depend upon vision and sensitivity of their whiskers – vibrissae.

The sensitivity of their eyes to light is ten times that of a human and is particularly sensitive to the colors of their bioluminescent prey. Like cats, they have a reflecting surface behind the retina, which roughly doubles their sensitivity. Their eyes permit clear vision both in water and in air. The powerful lens of their eye is responsible for most of the focusing, rather than the cornea. In addition, it takes only 2-3 minutes for elephant seals to adapt their vision from the bright ocean surface to the dark conditions at the bottom of their dive. In comparison, it would take humans 25 minutes to adapt to the same dark conditions.

Their elephant seal’s vibrissae pick up underwater vibration and tactile cues that contribute to successful foraging. The sensory information from the extensive neural connections at the base of each whisker help them to focus on and follow prey. Each of the approximately 100 whiskers on both sides of the face can sense the location of moving prey.

The whiskers may be a millimeter across (roughly 10 times the width of human hair) near the face. They arise from follicles that can be 3⁄4 “ long, much longer than the follicles in samples of molted hair. They have 5 to 10 time as many nerve endings as terrestrial mammal whisker follicles.

Each whisker has a blood supply as well, which helps to avoid the numbing effect of cold waters and to furnish the many nerves with needed oxygen. The whisker follicles are supplied with enough blood that even the skin around them is a few degrees warmer than the rest of the face.

Sonification

A study published in 2018 produced some results and a presentation that is very interesting.

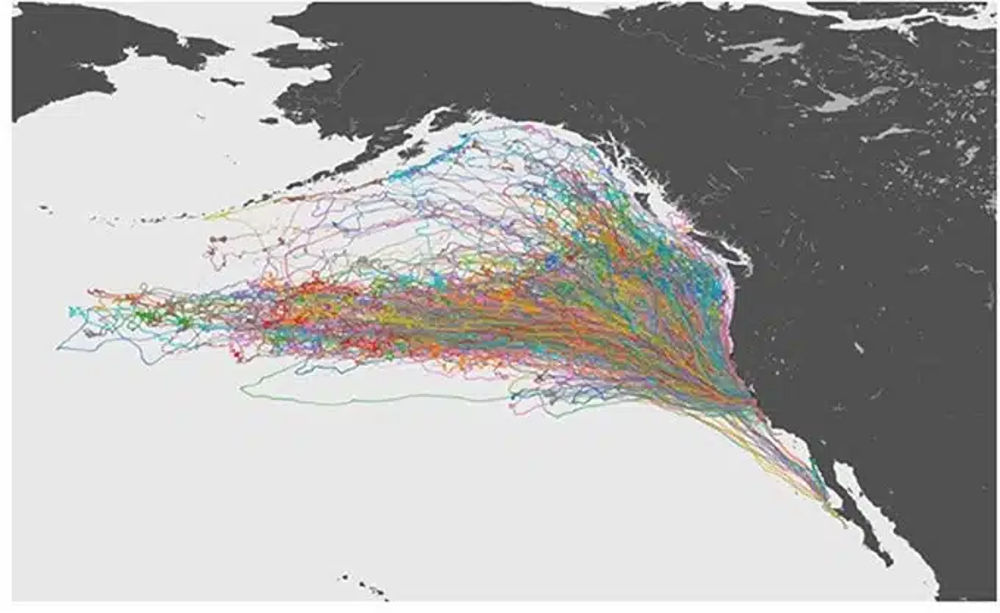

Data on the tracking of 321 adult female seals were used to produce a “chorus” that captured some characteristics of their sea voyages-roughly 80 days post breeding and 200 days post molting. Most of the seals were from Año Nuevo but 20 were from a colony on Islas San Benito, Mexico. The trips took place between February 2004 and May 2014.

Data collected were considerable: over 90,000 seal-hours and over 1 million individual positions. The purpose of the study was to explore the utility of an acoustic presentation of part of this collection of data. Each seal at sea contributes a tone that varies with latitude, lowering in frequency as it moves west. The combination of the tones of all the seals in the ocean at that time has a volume that depends upon the spread of the group: high when close together, low when widely separated.

Making Energy from Blubber

Elephant seals have a thick layer of blubber that keeps them warm in the deep, cold sea. Blubber is fatty tissue found under the skin in all pinnipeds.

Blubber is different from other types of fat, however, in that it is laced with blood vessels and collagen fibers. It functions as an insulating layer, keeping internal organs warm in an ocean environment below 40° F (4.5° C) and also keeps the seal buoyant and streamlined for efficient passage through water. In addition, elephant seals are able to metabolize their blubber, burning the fat for energy when they are fasting. Water is a by-product of blubber metabolism which allows them to survive extended periods of fasting.

Blubber may account for nearly 50% of an adult male’s weight at the beginning of the pupping and breeding season (December). By the end of breeding season in March, adult elephant seals of both sexes will have lost about 40% of their weight through blubber metabolism.

Thermoregulation

Seals control internal temperatures and reduce heat loss by a mechanism called countercurrent heat-exchange. As an example, the arteries carrying warm blood to the hind flippers are meshed with the veins carrying cold blood. Inside this mesh, heat is transferred from the arteries to the veins, moving heat to the returning blood rather than losing it to the ocean.

At times, the problem on land is removing excess heat from the body. This is accomplished in a number of ways, most prominent being by flipping the cool moist sand onto the body, cooling by contact and by evaporation. The seals will also from time to time raise a front flipper. There is very little blubber insulation in the “arm pit” and the blood flow is near the surface there, allowing efficient cooling. The seals will often line up along the water’s edge and use the cool wet sand as another means of releasing excess body heat.

Vital Statistics

Diving

The average dive depth of an elephant seal is 1,000 to 3,000 feet (300 – 900 meters) with a maximum depth of over 5,000 feet (1,500 meters). Read on below to learn more interesting facts about the elephant seals at each stage of their lives.

Elephant Seal Pup

Length at birth: 3 – 4 feet (1 meter)

Weight at birth: 60 – 80 pounds (27 – 37 kilos)

Weight at weaning: 300 pounds (135 kilos)

Coat Color: Black for first 4- 6 weeks

Elephant Seal Adult Female

Length: 9 – 12 feet (2.5 – 4 meters)

Weight: 900 – 1,800 pounds (400 – 800 kilos)

Coat Color: Blond to light brown

Elephant Seal Adult Male or Bull

Elephant Seal Adult Male or Bull

Length: 14 – 16 feet (4 – 5 meters)

Weight: 3,000 – 5,000 pounds (1,400 – 2,300 kilos)

Coat Color: Light to dark brown

Where Do They Spend Their Time?

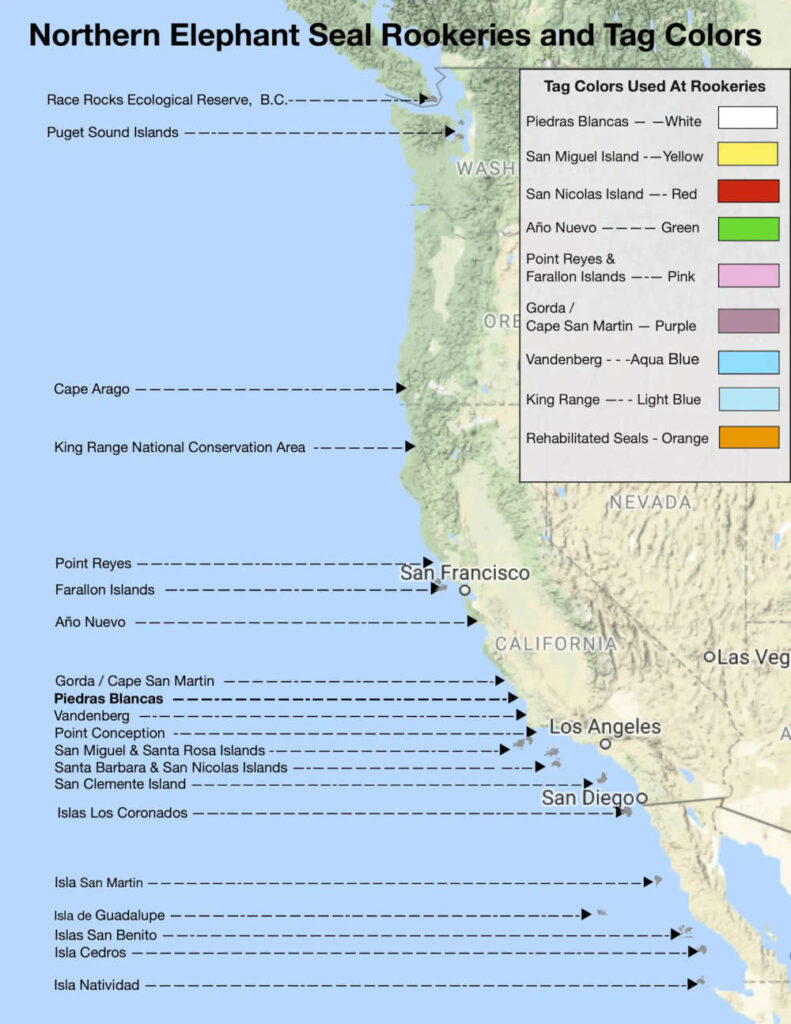

Northern elephant seals are found in the North Pacific, along the coast of North America, from Baja California, Mexico to the Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands. During the breeding season and molting periods, they live on beaches on offshore islands and a few remote spots on the mainland. The rest of the year elephant seals are at sea, well off shore (up to 5,000 miles, or 8,000 km), and may descend to over 5,000 feet (1,524 m) below the ocean’s surface.

There are several mainland locations to view the elephant seals along the California coast, as you can see in the map below, including Piedras Blancas, Año Nuevo State Park,and Point Reyes National Seashore.

The seals live solitary lives at sea for 8-10 months of the year, spending 90% of their time deep under water. They routinely dive 1,000 to 3,000 feet (300 to 900 meters), staying down an average of 25 minutes before returning to the surface to breathe for 2 – 3 minutes. However, individual seals have been known to dive to 5800 feet and to stay down as long as 2 hours. This behavior continues 24 hours a day for periods of several months, uninterrupted by visits to land or longer periods on the surface. Seals can travel 60 to 75 miles per day, but feeding slows them down to about 1/3 of that speed.

The male seals typically forage for food in focal feeding areas (blue spots along the coastline below), at the edge of the continental shelf, from Oregon to as far west as the Aleutian Islands. The shelf drops off into deeper water, an area called the continental margin, where the seals hunt for a variety of prey. Their feeding areas can be as far as 3,000 miles (5,000 km) from their rookery on the Central Coast of California.

The seals employ a grab and swallow technique of feeding, taking such prey as hake, dogfish, rays, octopus and crabs, generally from the ocean bottom. The danger from orcas is greater here than in mid-ocean depths, but the quantity and quality of food allow the adult males to gain the weight they need to survive their fasts in the rookery and the roughly five months a year travel time between the rookery and feeding ground. Their two foraging trips are approximately equal in length at four months for older males and five months for juveniles.

The female seals do not grow as large as the adult males. Females spend two more months at sea each year than males do. They forage primarily in deep mid-ocean water, typically feeding at depths well above the bottom. Their vast foraging area is indicated in the red spots on the map below. Recent evidence shows that their diet is primarily lantern-fish, hake and ragfish, with less than 10% squid.

Even during the day it is very dark in the deep water where they hunt for food. Their eyes are particularly sensitive to the bioluminescent colors of prey, such as lanternfish and squid, at their foraging depths.

Unlike the males, the two foraging trips of adult females are of quite different lengths – approximately 2.5 months between weaning their pup and returning to molt and 7.5 months between the end of the molt and birthing. During this longer second period, the female is nourishing her baby as well as herself. Evidence suggests that their daily food intake may average 20 kg (44 lbs.) and be as much as 32 kg (70 lbs.) per day. Weight gains of 1 kg (2.2 lbs.) per day at sea are typical for pregnant females.