The Northern Elephant Seal

Northern Elephant Seals (Mirounga angustirostris) are remarkable for their extreme adaptations to life in the ocean. They are capable of diving to depths exceeding 5,000 feet and can remain submerged for up to 70 minutes, feats made possible by their ability to store oxygen in their blood and muscles rather than their lungs. Their large, inflatable proboscis (in males) is not only distinctive but also serves as a resonating chamber for vocalizations used in dominance displays during mating season. Additionally, they undertake one of the longest migrations of any mammal, traveling up to 13,000 miles annually between feeding and breeding grounds. Adult males are significantly larger than females, weighing between 3,300 and 5,100 pounds (1,500 to 2,300 kg) and reaching lengths of 13 to 16 feet (4 to 5 meters), while females typically weigh between 880 and 1,980 pounds (400 to 900 kg) and measure 8.2 to 11.8 feet (2.5 to 3.6 meters) in length.

Seasonal Behaviors

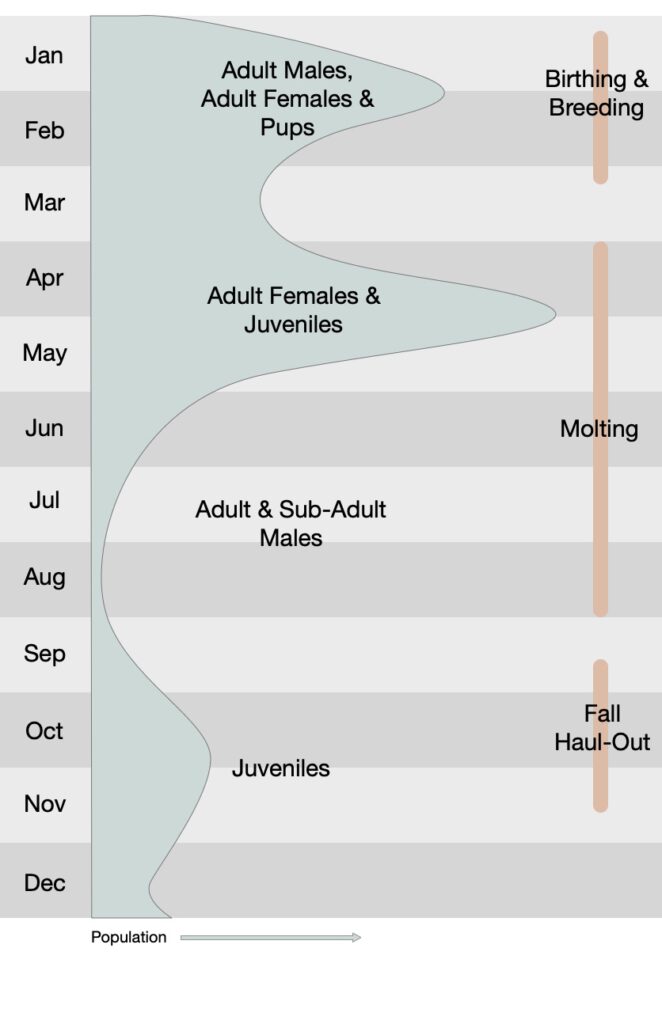

Northern elephant seals exhibit highly seasonal behaviors tied to reproduction, molting, and foraging. They spend about 90% of their lives at sea, only coming ashore twice a year. During the winter months (December to March), they gather at rookeries for birthing and mating, in locations extending from Vancouver Island in Canada, along the California Coast, and off Baja California in Mexico. Later in the year (April through August), they return to land to molt, shedding their fur and skin in a process known as “catastrophic molting”.

Appearance On Land

Elephant seals come ashore during two distinct periods: the breeding season from December through March and the molting season from April through August. During these times, they haul out onto remote beaches or islands that provide protection from predators and harsh weather. The timing of these events varies slightly by location, with some northern populations pupping later due to colder climates. The accompanying chart shows the elephant seal population at Piedras Blancas throughout the year.

Mating Cycle

The mating cycle is highly competitive and hierarchical. Male elephant seals arrive first at breeding sites in December to establish dominance through physical battles. Dominant males, or “alpha bulls,” form harems of 30–100 females. Mating occurs after females have given birth and nursed their pups for about four weeks. Only a small percentage of males successfully mate, while others remain on the periphery attempting opportunistic copulations.

Birthing

Females give birth shortly after arriving at rookeries, typically between late December and February. Each female births a single pup conceived the previous year. Pups are born weighing around 60–80 pounds and nurse on their mother’s rich milk, which is over 50% fat, allowing them to gain up to 10 pounds per day. After four weeks of nursing, mothers abruptly wean their pups and return to sea.

Molting

During the molting season, northern elephant seals undergo a unique process called “catastrophic molting,” where they shed their entire layer of fur and skin in a short period. This process is critical for maintaining their skin and fur health, as it allows them to replace old, worn-out layers with new ones. During molting, seals are unable to enter the water because their skin is sensitive and vulnerable to infection. They fast during this time, relying on stored fat reserves for energy. Molting typically lasts about a month, after which they return to the sea to resume feeding.

Feeding

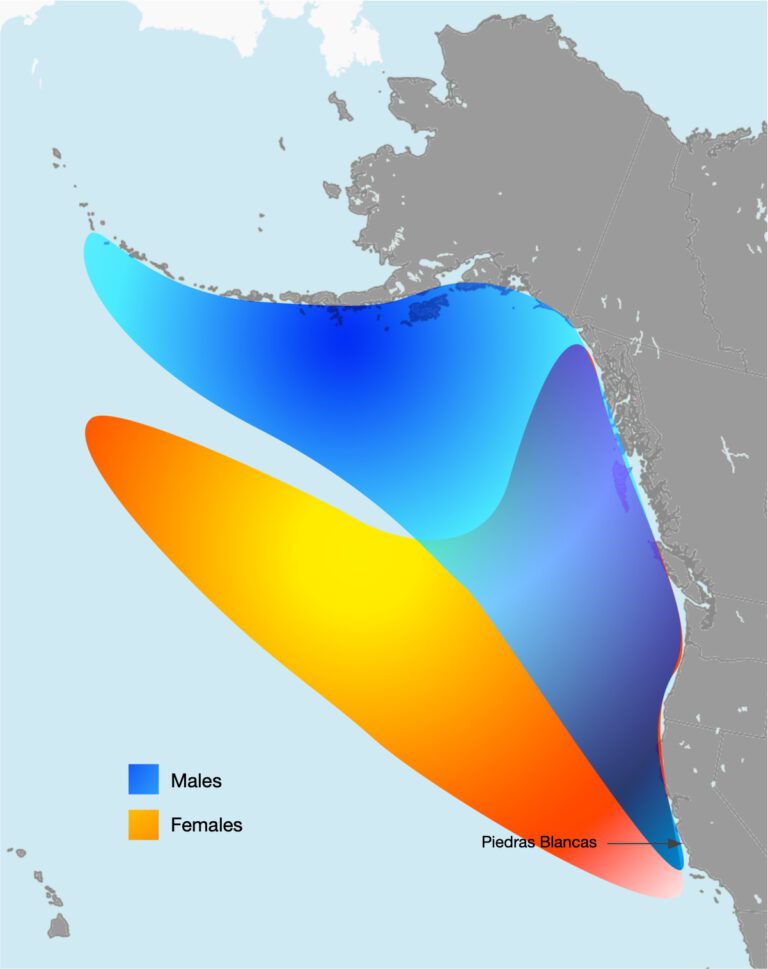

Northern elephant seals are solitary feeders that dive continuously while at sea. Males forage northward along coastal areas such as the continental shelf near Oregon, Washington, Alaska’s Gulf region, or even as far as the Aleutian Islands, consuming benthic prey like skates and small sharks. Females undertake longer and more westerly migrations into the open ocean waters, targeting pelagic prey such as squid and fish. Their deep-diving behavior helps them avoid predators like great white sharks and orcas while accessing abundant food sources. While males return to specific feeding grounds year after year, females display more variable routes. This sexual segregation reduces competition for resources but reflects different survival strategies: males prioritize energy-dense prey closer to land while females forage farther offshore in less predator-dense waters.

Conservation

Once hunted nearly to extinction in the 19th century, northern elephant seals have made a remarkable recovery due to legal protections like the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. Today, their population is estimated at over 200,000. However, threats such as entanglement in fishing gear, vessel strikes, and climate change continue to pose risks to their survival. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection and reducing human impacts on their marine environment. Friends of the Elephant Seal is committed to protecting the Northern Elephant Seal through educational initiatives that engage the public and, in collaboration with California State Parks, support docents at the Piedras Blancas Rookery.